|

| Weird |

Raggi has generally marked out the unique monster as the touchstone of the sub-genre and I first heard of him via his Random Esoteric Creature Generator (or possibly his "I hate fun" essay; I can't remember which exactly) which had the express purpose of obviating the need for a "monster manual" by having every monster be different. Likewise, LotFP has no book of monsters and all the monsters on the Raggi-produced Isle of Adventure are unique.

I don't feel this is a productive approach to the question of weirdness in the game world. Partly this is because it's a lot of work to keep coming up with new monsters for every single encounter, but also because I think is is actually counter-productive; the weird simply becomes mundane.

The "weird" is that which is outside the norm; the things that stand out from the background. But that background need not be like our world nor lack the existence of re-occurring monster types.

|

| Not Weird |

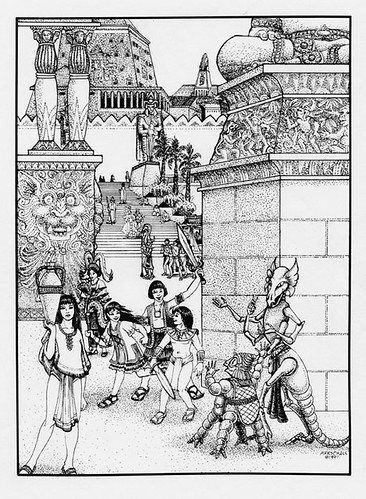

Once the underworld is entered, however, things change. Ancient crypts may contain anything from sentient clouds of eyes to incarnated weapons in the form of women whose kisses incinerate their lovers, to mouths with hairy legs. But all interspersed with "ordinary monsters" and human cultists as well as the various non-human races and alien technology.

Every campaign needs some bread-and-butter monsters and the repetitiveness of many supposedly unique monsters simply points up how hard it is to be original every time. AD&D's hoardlings and Glorantha's Broo actually become quite dull after a while as their randomness becomes their most distinctive characteristic. When everything is weird, nothing is.

To me the key to a good Weird Fantasy campaign is indeed uniqueness, but used sparingly; less than once per scenario. The background and its patterns of what counts as normal needs to be firmly established so that the players can genuinely feel a shock when those patterns are broken.

I've only managed to frighten players a couple of times at the table, and both times were by the use of unique monsters but the fact is that they only knew they were dealing with something unique and weird because they had internalized the rest of the fantasy world with its orcs and owlbears and so on; there was an established style which allowed their expectations to be undercut effectively.

It is possible to build a fantasy world where all monsters are unique but I think the only way to pull it off is to replace monsters generally with people - evil high priests, magicians, and lots of 0-level minion types - rather than to simply generate dozens of singular monsters and go on as if nothing had changed.

Interestingly, many of the monsters in the monster manual reflect this too, in that many of them are drawn from "real" myth and were originally imagined as being unique. The catoblepas was Weird Fantasy in the 16th century. The one and only chimera was a bizarre and unsettling combination of impossible characteristics 21 centuries before that.

But if I were to pick out one MM monster that has fallen the furthest from its Weird Fantasy original, it would be the minotaur.

The story of the minotaur is horrific and perverted in many ways. We tend to think of the Greek myths as something rather highbrow, but many of them are nothing more than horror stories obviously invented with the same aim as The Exorcist - a thin layer of religious moralizing used to excuse some gore and thrills.

So, Daedalus builds a fake cow for the queen of Crete to climb into so she can have sex with a bull. Depending on where you learned about the Minotaur this is either a bit of a shock, or you're so used to it as a part of the story that you don't really think about it. Think about it now; imagine it's a real news item about your own queen or first lady or whatever you have in your country. Imagine people's reaction.

But, hey, it gets better. The queen gets pregnant and has the child. It's half human and half bull (which half is which, is surprisingly not completely agreed upon in antiquity but the bull-headed version is the most popular); let that delivery room scene play out in your head for a moment too (and the version where the head is human too, why not?).

|

| No longer weird |

The Minotaur is a layer cake of freakishness piled on freakishness and the effect in the mind's eye of the listener at the plays written about it was exactly the one desired by Weird Fantasy writers - the skin crawling, hair-raising feeling of wrongness.

Yet the minotaur (little 'm') is one of the most tired and mundane of all fantasy tropes today, IMO. In many settings players can play a minotaur, meet other minotaurs, settle down, raise little minotaurs and run for mayor of Bullpen (pop. 103). About as bland a "monster" as one can imagine.

The minotaur illustrates two sides of the coin: the original shows what the essence of the Weird is - the feeling of wrongness that can be evoked even in a real world where real people believe that nature spirits inhabit practically every glade and hill and gods walk the Earth in human guise almost daily. Being supernatural is not Weird in itself, and you can have a deeply supernatural world of wonders without having to make everything unique.

On the other hand, uniqueness is vital to the Weird in that familiarity inevitably erodes shock. "Blink" was one of the best Doctor Who episodes of recent years; "Time of Angels" wasn't. The minotaur is a warning to everyone who thinks they can recapture the original atmosphere of a monster by bringing it back, especially bringing it back in numbers. What you get the second time is not Weird any more, no matter how dangerous you make it.

Right, juxtaposition of unfamiliar to familiar is exactly what makes for weird, and is why the contrast between dungeon and settlement works for D&D (as well as the reason why it can get stale).

ReplyDeleteAny overt play for "weird" can become tiresome after awhile - look at Lady Gaga - and I think that's another reason to have some returning monsters. Rather like the Klingons and Harry Mudd in Star Trek; they help ground the characters so that when things do go Tonto there's a contrast to play off.

ReplyDeleteI think you make a very valid point about it being very easy to overplay the weirdness card. I actually feel the same way about magic and fantastical elements as well. A little of it is exciting and exotic, but too much becomes boring and stifling.

ReplyDeleteI talk about this at length in my blog: http://gridpapergladiators.blogspot.com/2012/10/the-role-of-verisimilitude-in-d-part-2.html

One of the reasons I like T1 - Village of Hommlet so much is that the setting is so mundane. There's very little that's overtly fantastic or magical in the setting which allows it to serve as a nice backdrop for the more sinister doings of the Temple.

When the weird stuff does show up, it's much more shocking in comparison to the relatively boring and normal village of Hommlet.